Game ContentsDefinitionsHistory of GamesRelated pagesReferencesNavigation menuMy entire waking life

Games

worksportstelevisionKinectboard gamescard gamesplaying cardscomputergamesLudwig WittgensteinplaycompetitionRoger CailloisChris CrawfordJohan HuizingaculturesocietyHerodotusAsia MinordiceDiceancient Egyptancient GreeksGoChineseKoreaJapanGoogleartificial intelligencecomputer gameOXOphysicsAtari

Game

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

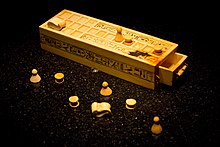

Senet the first known board game, made in ancient Egypt.

Go, the ancient board game created in China; it then passed to Korea and Japan.

This simple pie chart illustrates the timeline for the history of games.

1895 painting by Paul Cézanne depicting a card game.

Tug of war is an easily organized, impromptu game that requires little equipment

A game is something that people do for fun. It is different from work. In many games, people play against other people. Many sports are games.

There are different kinds of games using many kinds of equipment. For example, in video games, people often use controllers or their keyboard to control what happens on a screen, such as a television screens and computers ones too. There are also games that use your body, such as the Kinect.

In board games, players often move pieces on a flat surface called a board to often achieve something like getting to the end or differently in chess.

In card games, players use playing cards. Some games don't need any equipment but children and Youtubers mostly play computer games.

Contents

1 Definitions

1.1 Ludwig Wittgenstein

1.2 Roger Caillois

1.3 Chris Crawford

1.4 Homo Ludens

2 History of Games

2.1 Other definitions

3 Related pages

4 References

Definitions

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Wittgenstein was probably the first academic philosopher to address the definition of the word game. In his Philosophical Investigations,[1] Wittgenstein demonstrated that the elements (parts) of games, such as play, rules, and competition, all fail to correctly define what games are. He concluded that people apply the term game to a range of different human activities that are only related a little bit.

Roger Caillois

French sociologist Roger Caillois, in his book Les jeux et les hommes (Games and Men),[2] said that a game is an activity which is these things:

fun: the activity is fun to do

separate: the activity cannot happen everywhere or, all the time

uncertain: the people doing the activity do not know how it will end

non-productive: doing the activity does not make or do anything useful

governed by rules: the activity has rules that are different from everyday life

fictitious: the people doing the activity know that the game is not reality

Chris Crawford

Computer game designer Chris Crawford tried to define the word game[3] using a series of comparisons:

- Something creative is art if it was made because it is beautiful, and entertainment if it was made for money. (This is the least rigid of his definitions. Crawford acknowledges that he often chooses a creative path over conventional business wisdom, which is why only one of his 13 games is a sequel.)

- Something that is entertainment is a plaything if it is interactive. Movies and books are entertainment, but not interactive.

- If a plaything does not have any goals to complete, it is a toy. (Crawford notes that by his definition, (a) a toy can become a game element if the player makes up rules, and (b) The Sims and SimCity are toys, not games.) If a plaything has goals, it is a challenge.

- If a challenge does not have an enemy, it is a puzzle. If it has an enemy or enemies, it is a conflict. (Crawford admits that this is a subjective test. Video games with noticeably algorithmic artificial intelligence can be played as puzzles; these include the patterns used to evade ghosts in Pac-Man.)

- If the player can only do better at something than an enemy, and cannot hurt the enemy or slow him down, the conflict is a competition. (Racing and figure skating are competitions.) However, if attacks are allowed, then the conflict qualifies as a game.

Crawford's definition of a game is: an interactive, goal-oriented activity, with enemies to play against, and where players and enemies can interfere with each other.

Homo Ludens

Homo Ludens (Playing Man) is a book written in 1938 by Dutch historian Johan Huizinga.[4] It discusses the importance of the play element in culture and society. Huizinga suggests that play is a condition for the generation of culture.

History of Games

The first writer of history was Herodotus, an ancient Greek. He wrote a book called “The Histories” around 440 BC, which is nearly 2500 years ago. Some of the stories he wrote were not true, and we don't know if this is one of those.

Herodotus tells us about king Atys; he ruled about 5,500 [five thousand five hundred] years ago in a country called Lydia. His country was in western Asia Minor, near modern Greece. Atys had a serious problem; his lands had very little food because the climate was not good for agriculture. The people of Lydia demonstrated patience and hoped that the good times of plenty would return.

But when things failed to get better, the people of Lydia thought up a strange solution for their problem. The path they took to fight their natural need to eat – the hungry times caused by the unusually hard climate - was to play games for one entire day so that they would not think about food. On the next day they would eat, so eating occurred every second day. In this way they passed 18 years, and in that time they invented dice, balls, and all the games commonly played today.[5]

Games appear in all cultures all over the world, an ancient custom that brings people together for social opportunities. Games allow people to go beyond the limit of the immediate physical experience, to use their imagination. Common features of games include a finish that you cannot forecast, agreed upon rules, competition, separate place and time, imaginary elements, elements of chance, established goals and personal enjoyment. Games are used to teach, to build friendships, and to indicate status.

In his 1938 history book the Dutch writer Johan Huizinga says that games are older than human culture. He sees games as the beginning of complex human activities such as language, law, war, philosophy and art. Ancient people used bones to make the first games. Dice are very early game pieces. Games began as part of ancient religions. The oldest gaming pieces ever found – 49 [forty nine] small painted stones with pictures cut into them from 5,000 [five thousand] years ago – come from Turkey, so perhaps the history of Herodotus is true. One of the first board games, Senet, appears in ancient Egypt around 3,500 [three thousand five hundred] years ago. The ancient Greeks had a board game similar to checkers, and also many ball games.

The first reference to the game of Go occurs in Chinese records from around 2,400 [two thousand four hundred] years ago. Originally the game Go was used by political leaders to develop skill in strategy and mental skill. Knowing how to play Go was required by a Chinese gentleman, along with the skills of artistic writing or calligraphy, painting and the ability to play a musical instrument. These were regarded as the four most important skills. In ancient China, a gentleman had to pass a test in these four key skills in order to get a good paying job in the government. The Chinese brought Go to Korea, and it entered Japan around 1,500 [one thousand five hundred] years ago, and it has been popular ever since.[6]

In March of 2016 a Google computer program beat the best Go players in the world. Go is believed to be the most complex board game ever created. Is this computer program smarter than a person? Well, it did beat the South Korean Go master Lee Se-dol, and Lee was surprised by the result. He acknowledged defeat after three and a half hours of play. Demis Hassabis, who made the Google program, called it an important moment in history, because a machine beat the best person in the world in an intelligent game. Such computer programs rely on what is called artificial intelligence. Go is a two-player game of strategy said to have had an origin in China perhaps around 3,000 [three thousand] years ago. Players compete to win more territory by placing black and white “stones” on a board made up of 19 [nineteen] lines by 19 [nineteen] lines.[7]

The first computer game that was ever created was probably the game OXO by Alexander Douglas in 1952. It was a version of tic-tac-toe. But most people consider the first true computer game where players actually participate to be Tennis for Two developed in 1958 by the physics scientist William Higginbotham. He wanted to teach about gravity, the force of attraction between masses. These men who created the early computer games did not forecast the potential for the popular use of games, because at that period in modern history it took a small room full of computers to make these games work! Another early game was Spacewar! developed in 1961 by MIT university student Steve Russell. In 1972 the company Atari produced the Pong game which was a huge commercial success; being a commercial success means that it made a lot of money. This was the true beginning of computer games that could be played at home.[8]

Today, all around the world people spend more the 3,000,000,000 [three billion] hours a week playing computer games.[9] This is equivalent to more than 342,000 [three hundred and forty two hundred thousand] years!

Other definitions

- "A game is a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome". (Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman)[10]

- "A game is a form of art in which participants, termed players, make decisions in order to manage resources through game tokens in the pursuit of a goal". (Greg Costikyan)

- "A game is an activity among two or more independent decision-makers seeking to achieve their objectives in some limiting context". (Clark C. Abt)[11]

- "At its most elementary level then we can define game as an exercise of voluntary control systems in which there is an opposition between forces, confined by a procedure and rules in order to produce a disequilibrial outcome". (Elliot Avedon and Brian Sutton-Smith)[12]

- "A game is a form of play with goals and structure". (Kevin Maroney)[13]

Related pages

- Video game

- Puzzle

- Sports

- Toy

References

| The Simple English Wiktionary has a definition for: game. |

↑ Wittgenstein, Ludwig 1953/2002. Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-23127-7..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

↑ Caillois, Roger 1957. Les jeux et les hommes. Gallimard.

↑

Crawford, Chris 2003. Chris Crawford on game design. New Riders. ISBN 0-88134-117-7.

↑ Huizinga, Johan 1955. Homo ludens; a study of the play-element in culture. Boston: Beacon Press.

ISBN 978-0807046814

↑ McGonigal, Jane. 2011. Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. New York: Penguin Books. Print. Pages 5-6.

↑ History of Games. Wikipedia. 23 December 2016. Online.

↑ Choe, Sang-Hun and John Markoff. 9 March 2016. Master of Go Board Game Is Walloped by Google Computer Program. The New York Times. 23 December 2016. Online.

↑ Overmars, Mark. 30 January 2012. A Brief History of Computer Games. PDF. 23 December 2016. Online. Pages 2-3.

↑ McGonigal, Jane. 2011. Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. New York: Penguin Books. Print. Page 6.

↑

Salen, Katie & Zimmerman, Eric 2003., Rules of Play: game design fundamentals, MIT Press, p. 80, ISBN 0-262-24045-9CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

↑

Abt, Clark C. 1970., Serious Games, Viking Press, p. 6, ISBN 0670634905

↑

Avedon, Elliot & Sutton-Smith, Brian 1971., The study of games, J. Wiley, p. 405, ISBN 0471038393CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

↑

Maroney, Kevin 2001., My entire waking life, The Games Journal, retrieved 2008-08-17

Category:

- Games

(RLQ=window.RLQ||[]).push(function()mw.config.set("wgPageParseReport":"limitreport":"cputime":"0.224","walltime":"0.299","ppvisitednodes":"value":691,"limit":1000000,"ppgeneratednodes":"value":0,"limit":1500000,"postexpandincludesize":"value":12009,"limit":2097152,"templateargumentsize":"value":657,"limit":2097152,"expansiondepth":"value":15,"limit":40,"expensivefunctioncount":"value":0,"limit":500,"unstrip-depth":"value":1,"limit":20,"unstrip-size":"value":23512,"limit":5000000,"entityaccesscount":"value":0,"limit":400,"timingprofile":["100.00% 214.839 1 -total"," 85.63% 183.964 1 Template:Reflist"," 44.09% 94.717 3 Template:Cite_book"," 22.91% 49.212 1 Template:ISBN"," 14.32% 30.757 1 Template:Wiktionary"," 12.36% 26.558 1 Template:Sister"," 10.83% 23.274 1 Template:Side_box"," 9.15% 19.658 1 Template:Catalog_lookup_link"," 7.85% 16.867 4 Template:Citation"," 6.27% 13.481 1 Template:Error-small"],"scribunto":"limitreport-timeusage":"value":"0.094","limit":"10.000","limitreport-memusage":"value":2569152,"limit":52428800,"cachereport":"origin":"mw1338","timestamp":"20190722181757","ttl":2592000,"transientcontent":false););"@context":"https://schema.org","@type":"Article","name":"Game","url":"https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Game","sameAs":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q11410","mainEntity":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q11410","author":"@type":"Organization","name":"Contributors to Wikimedia projects","publisher":"@type":"Organization","name":"Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.","logo":"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://www.wikimedia.org/static/images/wmf-hor-googpub.png","datePublished":"2004-03-10T01:29:45Z","dateModified":"2019-06-08T22:58:33Z","image":"https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d7/Senet_game_pieces_%28Tutankhamun%29.jpg","headline":"entertainment, activity; structured playing, usually undertaken for enjoyment"(RLQ=window.RLQ||[]).push(function()mw.config.set("wgBackendResponseTime":143,"wgHostname":"mw1323"););